re:View – The 2015 Bookshelf

January: a journey to other worlds

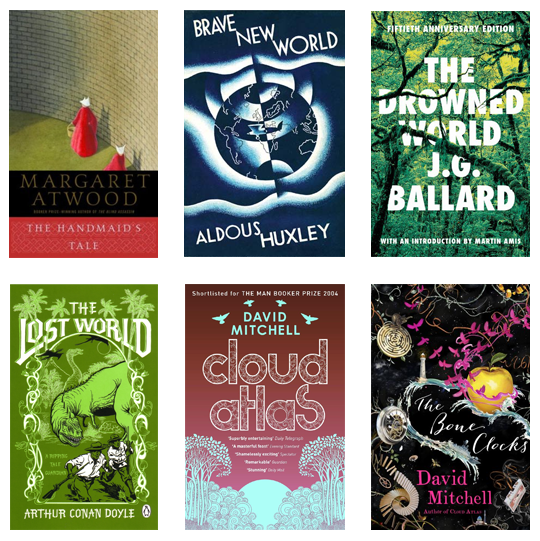

New year, new bookshelf! After finally picking up The Handmaid’s Tale I fancied some more alternative reality kind of stuff, so my reading journey throughout January took me from dystopian to prehistoric to post-apocalyptic worlds…and back again. Also as a new feature this year I’m trying to do Bookshelf on a monthly basis. I’ve still got quite a bit of otherworldly reading lined up so expect a similar theme for February.

As well as the books below I also read Emily St John Mandel’s Station Eleven, which has certainly been my book of the month and is, quite possibly, already my favourite book of the year. It’s so good it has earned its own dedicated review post. Check it out here – I really can’t recommend this book enough.

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Every now and then you come across a book that you want to shout about from the rooftops. The Handmaid’s Tale is one of them. To me this read like a female companion to Nineteen Eighty-Four; a feminist perspective on what we can expect in a fundamentalist, totalitarian society that could easily be waiting five years down the line. But more than that, it is a horror vision of an alternative present which seems terrifyingly possible and – even thirty years after its publication, perhaps more terrifyingly – actually feels increasingly plausible if you take a good look around and start thinking too much about what’s going on in the world. Like Orwell and Huxley before her, Atwood describes a scenario that will be chillingly relevant for any decade, past, present or future. It reminds us that we can never rule out the possibility of history repeating itself, no matter how scientifically advanced or socially progressive we have become – and it’s altogether possible that, because of this progress, the variations on history are becoming ever more horrible.

Pens: 5 out of 5

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

Oh brave new world; oh terrifyingly familiar new world. What really terrified me about this book is how predictive it is. Ok, maybe not the lab-grown and hypnopaedia-ed babies and the details of the political and social order, but just how spot-on is Huxley’s vision of the brain-washed masses living in a comfortable haze of mindless consumerism, meaningless sex and recreational drugs, while the less fortunate rot in their slums that aren’t deemed worthy of development? I mean, take a look around. Considering that Huxley wrote it in 1931, this book is amazingly relevant to this day. So, yes, some of the sci-fi looks rather quaint nowadays (They travel by rocket but still need lift operators, aw! They have fully automated bathrooms but still need to nip into buildings to use the telephone while they’re out, lol!) and the moral dilemma of the Savage seems helplessly classical from today’s perspective. But when it comes to seeing the direction humanity overall is heading, Huxley had a pretty good radar, I think.

Pens: 4 out of 5

The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard

A very weird dystopian novel in which Ballard ponders de-evolution and social regression, and the question whether we all have some deep-down genetic memory of our ancestors’ journey up the evolutionary ladder. Sparse in plot and characterisation, the novel is centered around a handful of characters stranded in one of the few patches of human civilisation left in a world submerged by climate change, where giant prehistoric lagoons and jungles, complete with once-extinct wildlife, create a dangerous and distorted paradise. As nature reclaims the last remnants of civilisation around them and increased solar radiation slowly drives them into madness, a group of biologists, soldiers and social exiles experience a strange transformation, their subconscious dragging their minds and bodies back in time to a prehistoric world that is encoded in their genes. Aesthetically the world Ballard creates is quite magical in all its devastated beauty, like an Atlantis with a scientific reality check, but the plot and characterisation – essentially a bunch of melancholy lunatics doing their best to kill themselves and each other – nearly drive you mad with ennui. But I’m guessing that’s the kind of vibe Ballard wants to get across, so in that case it certainly works. I’m in two minds about this book – I found it a bit annoying to read, but I do treasure the images of the drowned world that it has put into my mind.

Pens: 3 out of 5

The Lost World by Arthur Conan Doyle

I’ll admit I mainly read this because I loved the US TV adaptation from the late 90s as a kid. And for once I actually enjoyed the screen version more than the book – as far as they can even be compared, as the adaptation is only very loosely based on the location and characters. I’m sure at the time it was published in 1912, The Lost World was an exciting adventure, very Victorian in style and written in the form of a travel diary. Read nowadays it seems rather old-fashioned indeed, filled with pompous men of science, hopelessly racist stereotypes of ‘inferior’ indigenous tribes and a bit too much manly strutting around lecture halls and rainforests. The women, where they do appear on the fringes of the narrative, wail and faint in the usual style of the time. All this means the characters are just a little too flat, the narrative a little too predictive – unless you constantly remind yourself to put everything in the context of is time. While it has certainly inspired the genre, this is maybe not one of Doyle’s works that has aged very well.

Pens: 3 out of 5

Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell

There’s been a lot of hype around Mitchell in the last few years so I kind of felt like I should read one of his books, but none jumped out at me when I browsed the bookshops. I eventually picked up Cloud Atlas because it was on the throw-out pile at my in-laws’ house. It took me an unusually long time to read it, which is generally a sign that it isn’t going very well. What we have here is a collection of six different, seemingly random stories – a 19th century seafarer, a 20th century musician, a 1970s conspiracy thriller, with a bunch of dystopian / post-apocalyptic future visions thrown in for good measure – which the author invites us to believe are all connected by the central character of each story actually being the same person reincarnated. Because, you know, they all have the same birthmark. At least I hope that’s what the author invites us to believe, otherwise the whole exercise would be very pointless indeed. The reincarnation angle kind of clashes logically with the other narrative device the author employs to create a (somewhat forced) connection: Character A writes a journal that is read by character B, who writes some letters that are found by character C, who is actually in a book read by character D, who is actually in a film seen by character E – you get the idea. And isn’t it oh so meta! What’s missing is an actual connection that justifies this epic 600+ word box-in-a-box-in-a-box format, a message that brings it all together and makes it worth reading through hundreds of pages of tangents. I didn’t find that connection, so for me this remains a collection of random novellas, some engaging, some rather boring, joined together by an unnecessary, gimmicky narrative device, that could have been written in half the number of pages.

Pens: 2 out of 5 (on the basis that I really enjoyed two out of the six novellas)

The Bone Clocks by Davit Michell

I wasn’t too keen on another Mitchell after my disappointment in the over-hyped Cloud Atlas, but this one came as a present and the synopsis sounded quite up my alley. The Bone Clocks is essentially the life story of a woman interwoven with a fantasy subplot about an epic war between good and evil immortals. The book follows the life of Holly Sykes and those connected to her through a series of different first-person narrators as she unwittingly becomes a central party in a supernatural war, with causes and consequences spanning from her 1980s childhood to the lives of her grandchildren in a near-apocalyptic future. I did very much enjoy the human stories in the ‘real’ part of this book, and the fantasy plot added some extra thrills, but I found Mitchell’s excursion into the genre a bit on the clumsy side. The fantasy plot is quite predictable and the terminology sounds like it’s borrowed from a self-published teenage pop-fantasy ebook. The immortals ‘subspeak’ with each other, commit ‘psychoslaughter’ and ‘decant the souls’ of children into ‘Black Wine’ which they drink to gain eternal youth and psychokinetic powers. Language-wise that made me cringe a fair bit; I’d have expected more creativity and less cliché from a literary author. Despite the flaws of the fantasy side of things, and although Mitchell seems to suffer from chronic overwriteitis (by at least 200 pages in this case), this is definitely an enjoyable read, mostly thanks to kick-ass Holly and her very engaging life story.

Pens: 3 out of 5